Is there any research/study/survey/... that tried to estimate how many paper abstracts medical researchers read when preparing a clinical systematic review?

-

I'll be very surprised if such a study exists. What would be the objective? – Carey Gregory Dec 05 '17 at 03:00

-

@CareyGregory better understanding the process of creating systematic reviews. – Franck Dernoncourt Dec 05 '17 at 04:21

1 Answers

Even if this will be just a partial answer, it might help to "better understand the process of creating systematic reviews", as given in the comments.

One obvious answer to give here is: all of the abstracts have to be read, once the papers turn up "positive" within the (re-)search strategy for the literature. After all they have to be evaluated for inclusion or exclusion.

If the original question is meant to ask for the average number of studies actually used, i.e. a hard number of included papers into the review, then the answer is quite different:

From Terri Pigott: Advances in Meta-Analysis, Springer, 2012:

Another common question is: How many studies do I need to conduct a meta-analysis? Though my colleagues and I have often answered “two” (Valentine et al. 2010), the more complete answer lies in understanding the power of the statistical tests in meta-analysis. I take the approach in this book that power of tests in meta-analysis like power of any statistical test needs to be computed a priori, using assumptions about the size of an important effect in a given context, and the typical sample sizes used in a given field. Again, deep substantive knowledge of a research literature is critical for a reviewer in order to make reasonable assumptions about parameters needed for power.

It therefore depends on how well studied and researched a field or a research question is to select the reviewed papers from. Highly fashionable topics with controversy attached will have hundreds or thousands to choose from, niche interests, unprofitable venues perhaps only a few. To request a statistic across all of these fields of clinical systematic reviews is entirely possible. But one of the problems associated with meta-analyses is the so called garbage-in-garbage-out problem: such an undertaking – of not only "estimate how many paper abstracts medical researchers read when preparing a clinical systematic review?" but even precisely calculate that number – might be in danger of producing meaningless numbers, only useful for journalists or politicians.

One article providing just such a meta-meta-analysis does list such a number as requested in the question for the sub-field of psychology: 51 (range 5–81). (doi: 10.1080/00273171003680187 A Meta-Meta-Analysis: Empirical Review of Statistical Power, Type I Error Rates, Effect Sizes, and Model Selection of Meta-Analyses Published in Psychology.) But it also highlights the problems inherent with such an approach quite nicely:

- Effect Sizes and Heterogeneity in Meta-Analysis

- Model Choice:

Fixed-effects models were used with much greater frequency than random- effects models, often without overtly stating that such a model was being used. On the other hand, random-effects models were used with increasing frequency over time. Future studies should more routinely implement random-effects models given their greater validity from an inference standpoint.

Finally, it is important to consider that use of random-effects models will lower power for significance tests in most cases (i.e., when the between-study variance is greater than zero).

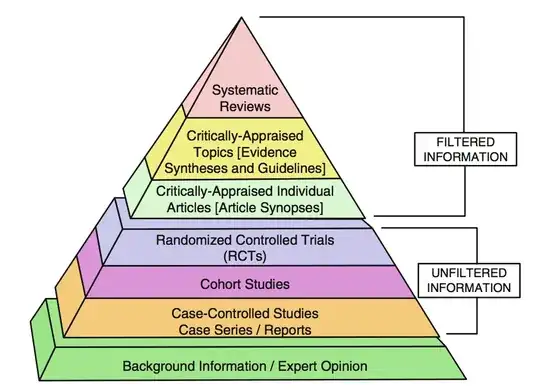

More general we might guard against blind trust into reviews or meta-analysis in general. Currently, the field of medicine strives to rebuild its knowledge on an evidence based foundation, which is of course very welcome. But in pursuing this goal with overly confident concentration on quantitative data and mathematical models, a child in the bathtub might get hurt. Naming, using or just believing in any kind of 'gold standard' (or variously even platinum) will be too much on one extreme side. That is pictured as follows:

The biggest problem with that picture is that "the filter" is quite ill defined and regularly studies with higher statistical power or greater significance are chosen to be included. While sounding logical at first this violates philosophical principles, on principle, like Carnap's "Principle of Total Evidence". This mechanistic reasoning introduces therefore its own set of systematic bias.

To address several of these known dangers, pitfalls and shortcomings the PRISMA statement is an initiative to at least standardise the approaches and document transparently the procedure chosen for these types of analyses.

More epistemological problems are condensed in Stegenga: "Is meta-analysis the platinum standard of evidence?" (2011):

[…] meta-analyses fail to adequately constrain intersubjective assessments of hypotheses. This is because the numerous decisions that must be made when designing and performing a meta-analysis require personal judgment and expertise, and allow personal biases and idiosyncrasies of reviewers to influence the outcome of the meta-analysis. The failure of Objectivity at least partly explains the failure of Constraint: that is, the subjectivity required for meta-analysis explains how multiple meta-analyses of the same primary evidence can reach contradictory conclusions regarding the same hypothesis. […] However, my discussion of the many particular decisions that must be made when performing a meta-analysis suggests that such improvements can only go so far.

For at least some of these decisions, the choice between available options is entirely arbitrary; the various proposals to enhance the transparency of reporting of meta-analyses are unable, in principle, to referee between these arbitrary choices. More generally, this rejoinder from the defenders of meta-analysis—that we ought not altogether discard the technique—over-states the strength of the conclusion I have argued for, which is not that meta-analysis is en- tirely a bad method of amalgamating evidence, but rather is that meta-analysis ought not be considered the best kind of evidence for assessing causal hypotheses in medicine and the social sciences. I have not argued that meta-analysis cannot provide any compelling evidence, but rather, contrary to the standard view, I have argued that meta-analysis is not the platinum standard of evidence.

- 6,897

- 2

- 23

- 60