Like the left ventricle, the right ventricle goes through a contractile cycle: at diastole, the pressure is near zero (and must be <0 relative to the right atrium, or it wouldn't fill with blood); at systole the pressure is maximal and drops quickly upon the end of contraction and closure of the pulmonary valve. Healthy right ventricular systolic pressure is typically less than 40 mmHg - far less than healthy peak left ventricular pressure which is normally stated as around 120 mmHg (like the right ventricle, the left ventricle is only briefly at such a high pressure; it decreases after the aortic valve closes).

Why is this so different from the left ventricle?

Similar to electricity, where voltage is a function of current and resistance (V=I*R), in a fluid system pressure is a function of flow and resistance.

Peak systolic pressure in the right ventricle is most related to resistance in the lungs; peak systolic pressure in the left ventricle is most related to resistance in the rest of the body. Typically, resistance in the lungs is much much lower than resistance in the rest of the body, but medical conditions that cause increased resistance in the lungs can cause pulmonary hypertension (which will also mean hypertension in the right ventricle).

Resistance in a vascular system is a function of both the total cross-sectional diameter of the vessels, and the length of the vessels. The path to the lungs from the heart is fairly short, and there is a very dense capillary bed.

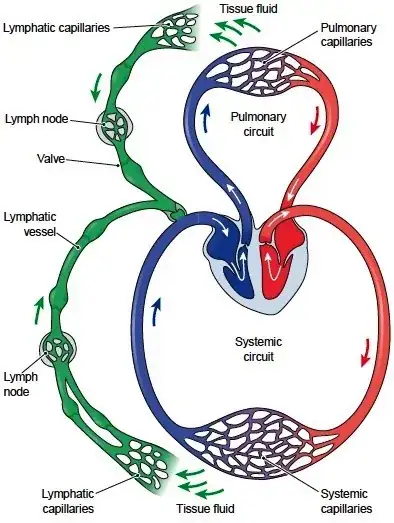

But what about the lymphatic system and differences in flow?

The lymphatic system doesn't factor in much at all, the volume of blood pumped by the right and left ventricles (and therefore flow) is almost exactly the same: the only exception would be any amount of fluid lost in the lungs (your diagram shows this with fluid entering the lymph system in the pulmonary circulation), which would actually mean less fluid pumped by the left versus the right. The presence of the lymphatic system only reduces the amount of flow through the distal veins: as your diagram shows the fluid is returned to the bloodstream prior to arriving in the right ventricle. There is no place for "extra" fluid to enter only the left-side circulation without first passing through the right.

Currie, P. J., Seward, J. B., Chan, K. L., Fyfe, D. A., Hagler, D. J., Mair, D. D., ... & Tajik, A. J. (1985). Continuous wave Doppler determination of right ventricular pressure: a simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study in 127 patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 6(4), 750-756.

McLaughlin, V. V., Archer, S. L., Badesch, D. B., Barst, R. J., Farber, H. W., Lindner, J. R., ... & Rubin, L. J. (2009). ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on expert consensus documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 53(17), 1573-1619.

Rudski, L. G., Lai, W. W., Afilalo, J., Hua, L., Handschumacher, M. D., Chandrasekaran, K., ... & Schiller, N. B. (2010). Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography: endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, 23(7), 685-713.