Short answer: Sophie Trudeau's positive test may still mean 3 : 1 odds of not having contracted Covid-19, but the odds could also be far more towards having Covid-19.

Justin Trudeau's negative test almost certainly means he was negative when tested. Of course, should Sophie be positive, that may have changed by now.

Update: I found a web page of the FDA listing tests that have this Emergency Use Approval. Each of them has manufacturer instuctions that list their test results towards the end. Some of the submitted test results use ≈100 negative samples in the clinical evaluation. But there is also one that has only 13 positive cases (all of which were correctly found) in their test - but that one got the emergency approval already early in February.

The latest 2 (by Thermo and Roche) used 60/60 and 50/100 cases for their clinical evaluation (all results correct). That gets the lower end of the confidence intervals for sensitivity and specificity to 94 - 97 % (with the lower end of the c.i. we'd thus have LR+ >≈ 20 or 17, expected values would be 61 or 51, respectively. For LR- <≈ 1/20 or 1/32 (expected 1/61 or 1/100).

Long version: Let's do some number juggling and see whether we can extract something useful. The following calculations are based on a somewhat worst-case scenario: the FDA emergency validation guidelines specify outcomes that such a new test in the current emergency situation must meet, and I calculate from the low end of performance that could be expected meet these criteria under somewhat unlucky circumstances.

So we know minimum performance requirements, but I do not know [yet] how good (= how much better than minimum performance) the tests are.

Sensitivity and Specificity

The starting point would be sensitivity and specificity of the respective test. I haven't found any published data on these, but the FDA has a Policy for Diagnostics Testing for Coronavirus Disease-2019 that says how labs that develop a test should do an "emergency validation". They can then get Emergency Use Approval.

- Sensitivity tells us: of all truly Covid-19-positive specimen, which percentage is correctly recognized as positive by the test; I'm going to use 87.5 % (see below)

- Specificity tells us: of all specimen that are truly negative for Covid-19, which percentage is correctly recognized by the test.

Sensitivity and specificity can be measured by standardized protocols, and they characterize the performance of the test.

From a patient's or doctor's point of view, however, they are not very useful numbers as they (we) need the answer to the inverse questions:

Predictive values

- positive predictive value PPV: given that the test yielded positive, what is the probability that the patient truly has the virus?

- negative predictive value NPV: given that the test yielded negative, what is the probability that the patient truly does not have the virus?

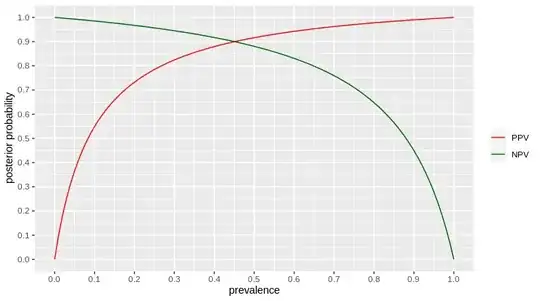

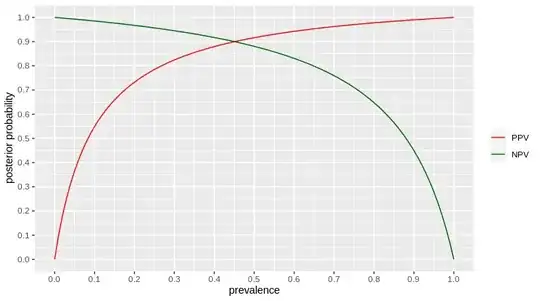

Predictive values can be calculated from sensitivity and specificity together with the prevalence (or, as we are talking about newly infected patients, the incidence) of virus among the tested population. Here's how they go for the assumed sensitivity and specificity:

red for positive test outcomes, dark green for negative test outcomes. posterior probability = after the test said something, what is the probability that the test result is correct = NPV for negative test result, PPV for positive test result.

Good estimates of prevalence are often difficult to obtain, because we need the prevalence among those who are tested and that is (and should be) quite different from the prevalence of the disease in the general population.

For some countries such as Italy, we have numbers of performed tests (Wiki page giving numbers for more countries): as of today (March 14th), they ran 109170 tests and have a total of 21157 cases. Not all tests are for initial diagnosis (AFAIK, a patient is considered cured only after a bunch of tests are negative), but as most cases are still "fresh", we may the ratio positive cases : tests run as one surrogate for the prevalence in the tested population. This would be around 20 % for Italy.

From the diagram we can then read for a new patient being tested the first time:

- if the test outcome is positive, chances are ≈ 75 % (or greater as I'm calcluating with the lower end of the possible range from the emergency validation) that the patient really has Covid-19.

So, up to 25 % false positives.

- if the test outcome is negative, chances are ≈ 95 % (or greater...) that the patient really does not have Covid-19.

So, up to 5 % false negatives.

Canada currently reports 25 positive out of a total of 796 tests, so about 3 % prevalence in the tested population.

For the USA, the CDC reports case numbers and test numbers, currently 1629 cases with (3995 + 15749) tests - but it is not entirely clear to me whether the populations completely coincide. Anyways, I'll use 8 % as guesstimate for prevalence.

| prevalence | PPV | NPV | Country/Population |

+------------+------+--------+--------------------+

| 3 % | 26 % | 99.6 % | Canada |

| 8-9 % (?) | 50 % | 98.8 % | USA, Germany |

| 20 % | 75 % | 95 % | Italy |

Now that is the population of "everyone who is tested". At least for Germany (March 14th) but probably also for Canada and the US, tests are done on people who show symptoms and on people that are known to have had contact with Corona virus cases: if they are found to be positive, they are sent home to quarantine and wait whether they did acutally catch the disease. But we may still say that the "people who are tested" population has subpopulations with and without symptoms.

So if there are further point of suspicion, say, the patient does cough, we'd say they belong to a high risk subpopulation with higher prevalence of Covid-19 compared to the overall prevalence among tested, so the chance of a false positive would be lower for them.

This will change as tests are performed only on people who show symptoms (by now, March 16th, everyone is already told to stay at home in Germany and self-isolate as well as possible - the test result will not change this in any way).

If we express the prevalence as odds (1 : 99 instead of 1 %), LR+ and LR- allow easy back-of-the envelope calculations.

LR+ = sensitivity / (1 - specificity) ≈ 11 or better for our test and

LR- = (1 - sensitivity) / specificity ≈ 0.05 = 1/20 or better for our test.

so they are indpendent of the prevalence and they tell us how the odds change due to the test: the posterior probability (predictive values) are the the pre-test odds multiplied with the likelihood ratio. In that sense, they tell us how much information we gain due to test (for positive and negative outcomes).

So, Canada reported odds of 25 positive : 771 negative tests. So for Sophie Trudeau, the odds went from 25 : 771 (or 3 %) to 25 : 771 * 11 = 273 : 771 ≈ 1 : 3 or 25 %. For Justin Trudeau 25 : 771 / 20 = 25 : 15420 ≈ 1 : 617 or 0.16 % of being Covid-19 positive (slight discrepancy to above due to rounding).

On the other hand, if we start testing more and more people for whom the risk of actcually having contracted the virus is lower and lower, we soon won't be able to draw meaningful conclusions from the test results any more: I'm in Germany, currently the federal info page lists 3800 confirmed cases. Even if we assume that there is a huge dark figure and in reality 20 x as many people are infected* that would be a prevalence in the general population of 0.1 %, the odds are 1 infected : 1.5 mio non-infected. If someone who does not belong to any particular risk group were tested positive, their odds would increase by factor 11, i.e. roughly 1 : 140000. A negative test result would decrease the odds by a factor of 1/20 to 1 : 31 mio. However, both results are of no practical use as they don't change the situation: pre-test situation is "very unlikely to be Covid-19 case", post-test situation is still "very unlikely to be Covid-19 case".

This is why, even if there were testing capacities for the whole population, tests don't make sense unless we know there are some risk factors such as some kind of respiratory disease or contact to someone who is known to have the virus. And why it is sensible to say that on slightly suspicious circumstances (= low, but not extremely low prevalence), one should self-quarantine/avoid contact but there's no point in testing [yet].

Detais on how I estimate sensitivity and specificity

- The lab first determines the limit of detection (LoD) for virus RNA. The LoD here is the lowest concentration at which 19 out of 20 replicate tests are positive (that would be 95 % sensitivity, but for samples spiked in the lab, but with a relevant and as difficult as possible matrix such as sputum).

Next, [leftover] clinical samples are used:

As there may not be any positive samples available, the lab can spike negative samples with virus RNA; a minimum of 20 samples are spiked within a range of 1 - 2 LoD plus 10 samples to cover the remaining clinical range.

Of these, at most 1 is allowed to have negative outcome (and that must be one in the lower concentration range). Thus, 29 positive out of 30 true positive.

Also 30 non-reactive specimens are tested. The policy doesn't say a number of false positives that is permissible, so I'm going to assume that must be zero.

The lab can then start with real patient samples. The first 5 positive and the first 5 negative cases must be confirmed by an approved test (and must all match).

Pooling the 2 "rounds" of testing clinical samples, we have:

- 34 (or 35) positive tests out of 35 truly positive specimen -> sensitivity at least 97 % with 95% credible interval 87.5 - 100 %,

specficity 100 % with 95% credible interval 92 - 100 %

There are additional checks required but they don't help us here.

Sampling errors are not included in this validation.

I'm not a clinical chemist, but I'm analytical chemist and in general analytical chemistry, that can easily be the dominating source of error. In that case, the above numbers would be useless.

Particularly the sensitivity may drop over time as the virus mutates.

To deal with this, in some cases multiple tests are done (read that in some newspaper article which I don't find at the moment).

When doing multiple tests, tests by different providers are used if possible: as they are developed from different virus samples, this gives a better coverage for mutations in the virus than doing the same test in replicate.

* Very handwavy scenario I derived from the development of case numbers in China after their quarantine/shutdown on Jan 26, assuming an incubation period of 2 weeks and that noone got infected after quarantine started.

Update Jun 3rd, 2020:

Results of a round robin test/ring trial in April in Germany on detection of SARS-CoV2 RNA (retrieved from https://www.instand-ev.de/en/eqas-online/service-for-eqa-tests.html#rvp//340/2003/)

- 7 samples: 4 positive for SARS-CoV2 covering a factor of 1000 in concentration of virus RNA; 3 negative for SARS-CoV: 1 negative for any coronavirus, 1 positive for HCoV OC43 but not SARS-CoV2 and 1 positive for HCoV 229E but not SARS-CoV2.

463 laboratories participated, submitting a total of 983 results per sample (1 lab can submit results for several methods)

The final evaluation comprises only 4 out of the 7 samples: while the ring trial was still ongoing, the ground truth and a preliminary evaluation was published for 3 samples in order to allow labs to use the results to adjust their procedure.

There was a problem with 24 labs (59 lab×methods) where results for two samples (the positive 1:100000 dilution and the negative with HCoV 22E) were interchanged.

I'll disregard these two samples for now.

Specificity was 969/983 = 98.6 % for the negative and 961/983 = 97.8% for the negative with HCoV OC43 (sample was unblinded).

The report notes that it is not clear whether the false positives are a result of the specificity of the method itself or whether they stem from contamination of the test samples with SARS-CoV2 in the labs.

Sensitivity was 980/983 = 99.7 % for the highest (sample was unblinded) and 914/983 = 93.0% for the lowest virus RNA concentration.

Such a ring trial measures the performance of diagnostic method and lab handling of the samples together.

Wenling Wang et al.: Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Types of Clinical Specimens, JAMA, 2020 May 12; 323(18): 1843–1844. reports on sensitivity of RT-PCR tests for various sampling procedure/locations. 1070 specimen collected from 205 confirmed Covid-19 patients.

They report 5 of 8 nasal swabs (95%c.i. 30 - 90%) to be positive and 126 of 398 pharyngeal swabs (95% c.i. 27 - 36%). This other study, while not primarily about PCR sensitivity reports about 60 %

The paper has very few details, e.g. on the point in time when samples were taken.

This study measures the sensitivity of method, lab handling and sampling procedure together.

Experts in radion interviews I heard over the last months were talking about sensitivity in the order of magnitude of 70 - 80 % due to difficult sampling (requiring trained staff, preferrably taking 2 swabs [but swabs were scarce at some point], the correct procedure for nasopharyngeal sampling being painful, the correct point in time wrt. the course of the disease)

In any case, the overall sensitivity seems to be dominated by sampling error rather than lab handling or the sensitivity of the RT-PCR.

So my initial guesstimates were too optimistic for overall sensitivity, but specificity looks better than the initial worst-case scenario: we have an LR⁺ of around 50, but LR⁻ is only about 1/4.

Important Note: all this is about the real time PCR tests for virus RNA. Antibody tests have their own and actually quite different characteristics.